Understanding the intricate dynamics of center-state relations is paramount for aspirants preparing for the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) examinations. The relationship between the central government and state governments in India is characterized by a complex interplay of political, administrative, and constitutional factors, reflecting the federal structure enshrined in the Indian Constitution.

The formation of the Indian Union didn’t arise from a pact between autonomous entities, and its constituent parts lack the ability to secede. Consequently, the Constitution outlines intricate regulations governing the interactions between the Center and the States.

All legislative, executive, and financial powers in India are allocated between the central government and the states as per constitutional provisions. The federal system aims for optimal coherence and coordination between the federal government and each state, facilitated by numerous constitutional provisions.

To better comprehend center-state relations, they can be categorized into legislative, administrative, and financial aspects.

1.Legislative Relations

Articles 245 to 255 of the Indian Constitution pertain to the legislative relations between the Center and the States. The Constitution divides legislative power between the Center and the States concerning both territories and subjects of legislation.

There are four key aspects of legislative relationships between the Union and the States:

- Territorial scope of central and state legislation.

- Allocation of legislative subjects.

- Parliamentary legislation in state domains.

- Center’s supervision over state legislation.

Territorial Extent of Central and State Legislation

The territorial extent of legislation in India distinguishes between the powers of Parliament and state legislatures. Parliament has the authority to enact laws that apply to the entire territory of India, including union territories and states.

State legislatures, on the other hand, can pass laws that are applicable either to the entire state or specific regions within it. However, for state laws to apply outside the state, there must be a significant connection between the state and the subject matter of the legislation.

Only Parliament has the jurisdiction to enact laws that have extraterritorial application. However, there are exceptions where parliamentary laws may not apply, such as in certain regions where the President or Governor has the authority to enact rules or direct modifications to parliamentary acts. These regions include the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Ladakh, Lakshadweep, and scheduled areas within states.

Distribution of Legislative Subjects

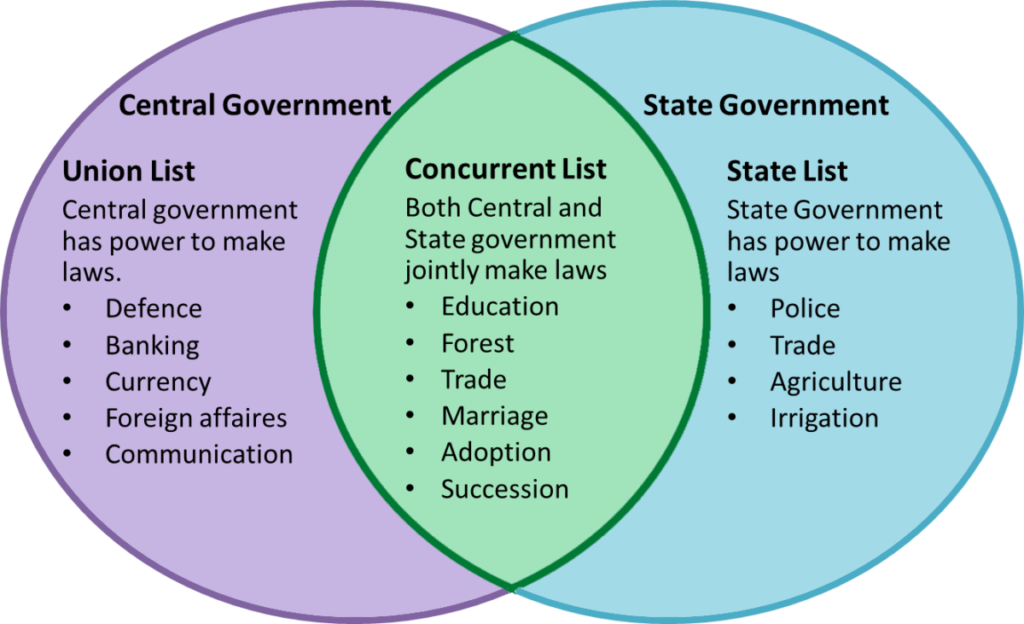

The Indian Constitution delineates legislative powers into three distinct lists: the Union List, State List, and Concurrent List. Exclusive authority over matters enumerated in the Union List lies with Parliament.

The State List predominantly grants legislative authority to state legislatures. Subjects listed in the Concurrent List allow both the central and state governments to legislate.

Parliament holds jurisdiction over laws concerning recurring themes.

In case of conflict, the Concurrent List takes precedence over the State List, and the Union List supersedes the State List.

Parliament possesses the power to legislate on residuary subjects.

Parliamentary Legislation in the State Field

The Constitution allows Parliament to legislate on topics listed in the State List under five exceptional circumstances:

- If Rajya Sabha passes a resolution with the support of two-thirds of the members present and voting, granting Parliament the authority to enact laws on a State List issue deemed beneficial for the nation. This resolution remains valid for one year and can be renewed multiple times, each time for up to a year. Laws enacted under this provision cease to be effective six months after adoption. In case of conflict between state and central laws on the same issue, central law prevails, although states may still enact legislation.

- During a National Emergency, Parliament can pass laws on any subject in the State List. However, such laws are valid for only six months before they expire. States retain the right to enact laws on these matters, but central laws take precedence in case of conflict.

- If a state requests Parliament, through a resolution, to legislate on certain issues from the State List, Parliament gains the authority to do so. Upon approval of this resolution, the state relinquishes its legislative rights over these matters.

- Parliament can legislate on subjects in the State List to implement international treaties, agreements, and conventions.

- When President’s Rule is imposed in a state, Parliament is empowered to make laws on any matter in the State List.

Centre’s Control Over State Legislation

As per the Constitution, the central government possesses authority to exert influence over state legislative matters through the following means:

- The governor can reserve specific laws enacted by the state legislature for the President’s consideration, placing them entirely under the President’s jurisdiction.

- Bills concerning certain subjects listed in the State List, such as interstate trade and commerce, can only be introduced in the state legislature with prior consent from the President.

- In the event of a financial emergency, the President may request a state to withhold money bills and other financial bills for his consideration.

2. Administrative Relations

The allocation of legislative powers has led to a shared executive branch between the central government and the states. Articles 256 to 263 of the Constitution address the administrative relationship between the Center and the States.

Distribution of Executive Powers

- The central government has authority over the entire nation concerning issues within its exclusive jurisdiction (Union List) and when exercising rights granted by treaties or agreements.

- Subjects enumerated in the State List are under the jurisdiction of the respective states.

- States hold executive authority over matters listed in the Concurrent List.

- The state executive must ensure compliance with laws enacted by Parliament.

- The executive power of a state must remain unaffected and free from interference.

The constitution imposes two restrictions on the executive authority of the states to allow ample room for the center to exercise its executive power without hindrance.

The state executive must ensure adherence to laws enacted by Parliament.

The state executive must not encroach upon or undermine the executive authority of the center within the state.

In both instances, the center is empowered to issue necessary directions to the state.

These directives from the center carry coercive force.

Article 365 stipulates that if any state fails to comply with the directives of the center, the President can declare that a situation has arisen where the state government cannot function in accordance with the Constitution. This implies that in such circumstances, the President’s rule can be imposed in the state under Article 356.

Centres advice over state

In Center-State Relations, the Center may offer guidance to states under the following circumstances:

- Development and upkeep of communication systems identified as crucial for national or military purposes by the government.

- Measures to ensure the safety of state railways.

- Allocation of adequate resources for elementary education in the native language of students from linguistic minority communities.

- Implementation of targeted programs for the welfare of Scheduled Tribes across different states.

Delegation of Functions

- To mitigate rigidity and avoid deadlock, the constitution allows for the intergovernmental delegation of executive powers.

- With the consent of the state government, the President can delegate the executive functions of the Union to it.

- Likewise, with the approval of the central government, the Governor may delegate the executive responsibilities of the state to the Union.

- This delegation of authority may be either conditional or unconditional.

- Additionally, the constitution permits the state to confer executive authority upon the Union without the state’s consent.

- However, such delegations are enacted by Parliament, not by the President. It’s important to note that the executive authority of a state cannot be transferred in a similar manner.

Cooperation Between Centre and States

- The following provisions have been incorporated to ensure cooperation and coordination between the center and the states:

- Parliament is empowered to adjudicate on any disputes or grievances regarding the utilization, allocation, and management of water resources of interstate rivers and river valleys.

- The President possesses the authority to convene an inter-state council to examine and deliberate on matters of mutual interest between the center and the states.

- There is a mandate for all of India to accord full faith and credit to the public actions, records, and judicial proceedings of both the central government and each state.

- Parliament is vested with the authority to designate the appropriate authorities for fulfilling the constitutional requirements pertaining to interstate trade, commerce, and intercourse.

All India Services

- In 1947, the Indian Civil Service (ICS) and Indian Police (IP) were replaced by the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and Indian Police Service (IPS), marking a significant transition in India’s administrative landscape.

- Established in 1966, the Indian Forest Service (IFS) became the third all-India service in the country.

- Members of the All India Services hold key positions at both the central and state levels, although their recruitment and training are overseen by the central government.

- While the central government retains ultimate control, immediate supervision is vested in the state governments.

- Article 312 of the Indian constitution grants Parliament the authority to establish an all-India service, subject to a resolution passed by the Rajya Sabha.

- These services amalgamate to form a unified entity with standardized pay scales, entitlements, and status.

- The primary objectives of the All India Services include maintaining high administrative standards across the federal and state governments, ensuring uniformity in the administrative framework nationwide, and fostering collaboration and cooperation between the central and state governments on mutual concerns.

Integrated Judicial System

- India, despite its federal structure, has established a unified judicial system responsible for interpreting and enforcing laws at both the federal and state levels.

- High court judges are appointed by the President of India after consulting with the Chief Justice of India and the respective state’s governor, and the President holds the authority to transfer or dismiss them.

- Additionally, Parliament has sanctioned the establishment of joint high courts to serve multiple states, further streamlining the judicial process.

Emergency

- In times of a national emergency, the central government holds the power to issue directives to the states on any matter, bringing the state governments under its complete control without suspending them.

- Under President’s Rule in a state, the President has the authority to exercise the functions and powers of the governor or any other administrative authority within the state.

- During a Financial Emergency, the President may issue significant orders, such as reducing the salaries of high court judges and state personnel. Additionally, the central government may mandate states to adhere to financial integrity principles.

3. Financial Relations

Article 268 to 293 of the constitution deals with Centre-State Financial Relations.

Allocation of Taxing Power

The exclusive authority to levy taxes on subjects listed in the Union list rests with Parliament.

Only the state legislature has the authority to impose taxes on matters listed in the State list.

Subjects listed in the Concurrent list can be taxed by both the state and the union governments.

Parliament holds the residual power to levy taxes.

Restriction on State’s Taxation Power

The authority to levy taxes on occupations, trades, callings, and professions lies with the state legislature, with a restriction that no individual should pay more than Rs 2500 annually.

States have the power to impose taxes on the sale or purchase of goods, except for newspapers. However, certain limitations apply:

- Sales or purchases conducted outside the state boundaries are not subject to taxation.

- Transactions related to imports or exports are exempt from taxation.

- Interstate trade or commerce transactions cannot be taxed.

- Taxes on goods essential for interstate trade and commerce are subject to regulations set by Parliament.

Electricity consumed by or supplied to the central government, as well as electricity used for railway operations, is not taxable by the states.

States may levy charges on water or electricity supplied to interstate river authorities established by Parliament, provided such imposition is approved by the President.

Distribution of Tax Revenues

Taxes imposed by the central government are collected and utilized by the state as per Article 268. The revenue generated from these taxes, such as excise duties and stamp duties, is deposited into the state’s consolidated fund.

Article 269 deals with taxes on goods involved in interstate commerce, and the revenue collected from these taxes is also deposited into the state’s consolidated fund.

While the central government imposes and collects taxes, the proceeds are shared with the states according to Article 270, excluding taxes mentioned earlier, surcharges, and cess. The allocation of these taxes is determined by the President based on recommendations from the Finance Commission.

Surcharges and cess mentioned in Articles 269 and 270 can be enacted by Parliament at any time, and the revenue generated from these goes to the central government.

State-exclusive taxes, which are listed in the state list, include taxes on agricultural income, excise duties on alcohol, profession-specific taxes, and property taxes, among others.

Distribution of Non-Tax Revenues

The centre’s primary non-tax revenue sources are as follows:

- Postal and telegraph services

- Railroads

- Banking

- Broadcasting

- Coinage and currency

- Central public sector enterprise

- Escheat and lapse.

The main sources of non-tax revenue for states are as follows:

- Irrigation

- Forests

- Fisheries

- State public sector enterprise

- Escheat and lapse.

Grants in Aid

The Constitution allows for state grants-in-aid to be provided by the central government. These grants can be categorized into two types: statutory grants and discretionary grants.

Statutory Grants:

Article 275 of the Constitution empowers Parliament to allocate grants to states based on their specific needs rather than distributing them uniformly among all states.

These grants are not fixed amounts and may vary for different states. They are allocated annually to the Consolidated Fund of India and disbursed to the states based on the recommendations of the Finance Commission.

Discretionary Grants:

Article 282 empowers both the central government and the states to allocate grants for any public purpose, regardless of whether it falls under their respective jurisdictions.

The decision to provide such grants rests entirely with the central government, which is not obliged to offer these subsidies.

Other grants:

The Constitution allowed for a one-time contribution for a specific purpose. Grants for jute and jute products in lieu of export duties were permitted for the states of Assam, Bihar, Odisha, and West Bengal.

According to the recommendation of the Finance Commission, these grants were to be provided for a period of ten years from the adoption of the constitution.

Challenges in centre state relations

- Centre-state relations are marked by disputes over resource allocation, legal challenges to central legislation by states, misuse of Article 356, and controversies surrounding the role of governors.

- Contentions over resource distribution, encompassing funds, taxes, and other entitlements, frequently arise between the Centre and states. Despite efforts to streamline revenue collection and sharing through the GST, there are ongoing concerns regarding the criteria employed by the Finance Commission for revenue allocation.

- States occasionally contest central laws in court, as seen with Kerala and Chhattisgarh challenging the constitutionality of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Investigation Agency Act, respectively.

- Article 356, allowing the Centre to impose President’s Rule in states, has faced criticism for being exploited for political purposes rather than addressing genuine constitutional crises. Incidents in Arunachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand underscore this issue.

- Furthermore, tensions emerge regarding the appointment and role of governors, with the Centre’s authority in their selection and their perceived use as tools to exert central power being contentious points.

Recommendations on centre state relations

Administrative Reforms Commission

- The Administrative Reforms Commission’s establishment, the formation of an interstate council per Article 263 of the constitution, and the appointment of governors possessing significant expertise in public service and impartial perspectives represent significant measures aimed at enhancing governance.

- States have been endowed with considerable authority, signaling a shift towards decentralization.

- To lessen states’ dependence on the central government, it is imperative to allocate more financial resources to them.

- State authorities have the discretion to request or independently deploy federal armed forces within their borders.

Sarkaria Commission Recommendations

- Establishing a permanent inter-State Council as per Article 263.

- Article 356 should be employed judiciously and only when necessary.

- Strengthening the institution of all-India services.

- Residuary taxation powers should be vested in the parliament.

- States should be provided with the rationale behind the President’s veto of state legislation.

- While the Centre should have the authority to deploy its military forces without state consent, consultation with states would be preferable.

- The Centre should engage in consultations with states before legislating on concurrent list subjects.

- Governors should be permitted to serve out their full five-year terms.

- The appointment of a Linguistic Minority Commissioner should be prioritized.

Punchhi Commission Recommendations

- The impeachment process is employed to oust governors upon completion of their five-year term.

- The Union should exercise caution when asserting Parliamentary authority in matters delegated to the states.

- Specific criteria were outlined for the selection of governors:

- They should possess expertise in certain fields.

- They must not be residents of the state.

- They should be impartial figures who refrain from engaging in local politics.

- They should not have recently entered politics.

The tenure of the government should be restricted to five years.

Governors could be subjected to a similar impeachment process as that of the president.

Effective coordination and collaboration between the Central Government and State Governments are fundamental aspects of India’s federal structure. Their joint efforts are aimed at ensuring the safety and welfare of Indian citizens, addressing issues such as counterterrorism, family welfare, environmental protection, and socio-economic development. The ongoing interactions between the center and the states have played a significant role in shaping the nation’s development trajectory. Enhanced Centre-State relations have led to improvements in governance at the national level, a more efficient administrative apparatus, and the integration of diverse communities into the broader societal fabric.