In the grand tapestry of governance, the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) stand as guiding stars illuminating the path towards a just and equitable society. Embedded within the framework of the Indian Constitution, these principles serve as a moral compass, directing the state machinery towards the welfare of its citizens. For aspirants gearing up for the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) examinations, understanding the essence and significance of DPSP is not just a requisite but a fundamental aspect of comprehending the socio-political fabric of India.

The Directive Principles of State Policy, enshrined in Part IV of the Indian Constitution, encompass a set of guidelines and ideals aimed at fostering social, economic, and political democracy in the country. Although not enforceable by courts, these principles hold immense moral and political significance, acting as a blueprint for the government’s policies and legislative actions.

The Sapru Committee in 1945 proposed two classifications of individual rights: justiciable and non-justiciable rights. Fundamental rights fall under the category of justiciable rights, while Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) fall under the non-justiciable category.

DPSP serve as guiding principles for the state to consider when formulating policies and laws. Various definitions of DPSP include:

- They are akin to “instrument of instructions” outlined in the Government of India Act, 1935.

- They aim to establish economic and social democracy within the nation.

- DPSPs represent ideals that are not legally enforceable by courts if violated.

- The source of Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) is the Spanish Constitution from which it came in the Irish Constitution.

Features of DPSP

The key characteristics of the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) outlined in the Indian Constitution are as follows:

- Constitutional Guidance: DPSPs serve as constitutional guidelines for the state in legislative, executive, and administrative matters. They provide ideals for the state to consider while formulating policies and laws.

- Non-Justiciable Nature: Unlike Fundamental Rights, DPSPs are non-justiciable, meaning they cannot be legally enforced by courts if violated. Governments are not obligated to implement them.

- Welfare State Objective: DPSPs aim to achieve the ideals of Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity as outlined in the Preamble. They embody the concept of a ‘Welfare State.’

- Socio-Economic Democracy: DPSPs encompass comprehensive economic, social, and political programs to establish socio-economic democracy in the country, contributing to the formation of a modern democratic state.

- Promotion of Good Governance: DPSPs allow for adaptability and innovation in governance to fulfill socio-economic development objectives, promoting good governance practices.

- Resemblance to ‘Instrument of Instructions’: DPSPs bear resemblance to the ‘Instrument of Instructions’ in the Government of India Act of 1935, as observed by Dr. Ambedkar.

- Judicial Aid: Despite being non-justiciable, DPSPs assist courts in assessing the constitutional validity of laws. If a law aligns with a Directive Principle, it may be considered ‘reasonable’ concerning Articles 14 and 19 of the Constitution.

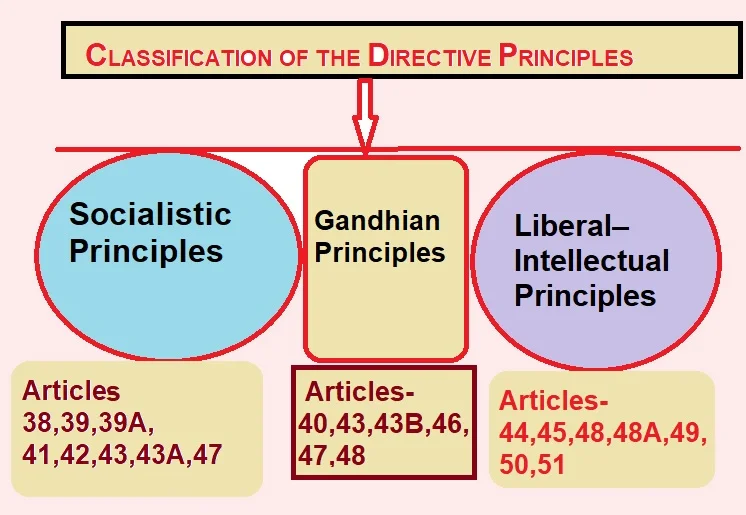

Classification of DPSP

While the Constitution does not explicitly categorize the Directive Principles, they can be broadly classified into three categories based on their content and orientation:

- Socialistic Principles

- Gandhian Principles

- Liberal-Intellectual Principles

Socialistic Principles

Article 38 of the Indian Constitution mandates that the State must endeavor to enhance the welfare of the people by establishing a social order that ensures social, economic, and political justice while minimizing disparities in income, status, facilities, and opportunities.

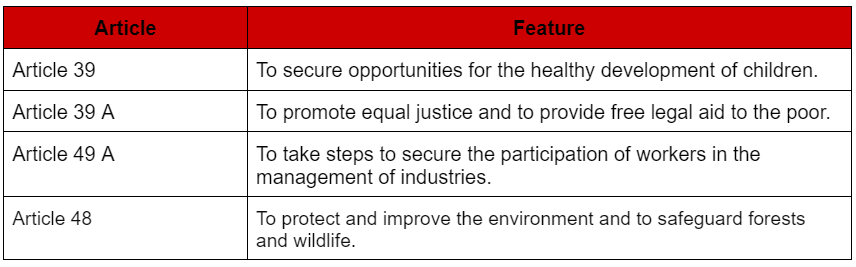

Articles 39 outline specific policies that the State should adopt to achieve this goal, including ensuring the right to an adequate livelihood for all citizens, organizing ownership and control of resources for the common good, preventing the concentration of wealth, guaranteeing equal pay for equal work regardless of gender, protecting the health and strength of workers, and prohibiting the exploitation of children and youth.

Article 41 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to work, education, and public assistance for individuals in cases of unemployment, old age, sickness, and disability.

Article 42 mandates that the State must ensure fair and humane working conditions and provide maternity relief.

Article 43 directs the State to strive towards securing a living wage and a decent standard of living for all workers.

Article 43A specifies that the State should take measures to facilitate the participation of workers in the management of industries.

Article 47 aims to elevate the nutritional levels and standard of living of the populace while enhancing public health.

Gandhian Principles

Article 40: The State shall take steps to organise village panchayats as units of Self Government

Article 43: The State shall endeavour to promote cottage industries on an individual or cooperative basis in rural areas.

Article 43B: To promote voluntary formation, autonomous functioning, democratic control and professional management of cooperative societies.

Article 46: The State shall promote educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people particularly that of the Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs) and other weaker sections.

Article 47: The State shall take steps to improve public health and prohibit consumption of intoxicating drinks and drugs that are injurious to health.

Article 48: To prohibit the slaughter of cows, calves and other milch and draught cattle and to improve their breeds.

Liberal-Intellectual Principles

Article 44: The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizen a Uniform Civil Code through the territory of India.

Article 45: To provide early childhood care and education for all children until they complete the age of six years.

Article 48: To organise agriculture and animal husbandry on modern and scientific lines.

Article 48A: To protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife of the country.

Article 49: The State shall protect every monument or place of artistic or historic interest.

Article 50: The State shall take steps to separate judiciary from the executive in the public services of the State.

Article 51: It declares that to establish international peace and security the State shall endeavour to:

Maintain just and honourable relations with the nations.

Foster respect for international law and treaty obligations.

Encourage settlement of international disputes by arbitration.

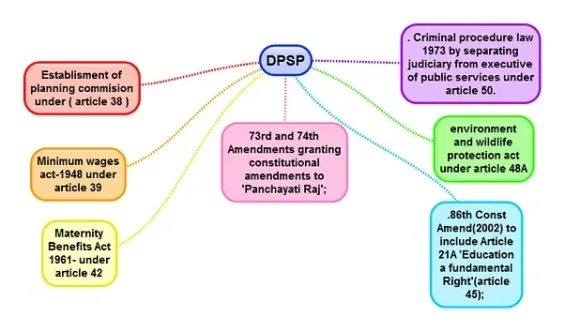

New DPSP

The 42nd Amendment Act of 1976

The 42nd Amendment Act of 1976 added four new Directive Principles to the list.

The 44th Amendment Act of 1976

BY 44th Amendment one more DPSP was added in the constitution.

86th Constitutional Amendment Act of 2002

The 86th Constitutional Amendment Act of 2002 introduced two alterations concerning the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSPs):

- It modified the content of Article 45, requiring the State to ensure early childhood care and education for all children up to the age of six.

- It elevated elementary education to the status of a Fundamental Right, enshrined under Article 21A of the Constitution.

The 97th Amendment Act of 2011

Application of DPSP

Instrument of Instructions: DPSPs serve as “Instruments of Instructions,” providing general recommendations to all authorities within the Indian Union, reminding them of the objective of constructing a new socio-economic order.

Framework for State Actions: They establish a comprehensive framework guiding all actions, including legislative and executive decisions, taken by the State.

Aid Judiciary: DPSPs assist the judiciary in assessing the constitutional validity of laws, serving as guiding principles for the courts.

Help Realize Constitutional Objectives: They elaborate on and strive to achieve the ideals outlined in the Preamble, including Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, for all Indian citizens.

Stability and Consistency in Policies: DPSPs contribute to stability and consistency in domestic and foreign policies across various domains, such as politics, economics, and society.

Supplement Fundamental Rights: DPSPs complement fundamental rights by addressing social and economic rights, filling gaps within Part III of the Constitution.

Help Realize Socio-Economic Democracy: By aiming to establish socio-economic democracy, DPSPs create an environment conducive to citizens fully enjoying their fundamental rights.

Help Measure Government Performance: DPSPs serve as benchmarks for evaluating government performance, aiding both citizens and opposition parties in scrutinizing government policies and programs.

Criticism of DPSP

Non-Justiciability: The fact that DPSPs are non-justiciable has led to criticism, as many argue that they have remained mere expressions of good intentions without legal enforceability.

Illogical Arrangement: Critics highlight the disorganized arrangement of DPSPs, which lacks a consistent philosophical basis. This mix of relatively trivial matters with crucial socio-economic issues and the juxtaposition of outdated and modern concerns have been pointed out as flaws.

Conservative Nature: Some critics contend that DPSPs are rooted in the political philosophy of 19th-century England and do not adequately address the needs of contemporary India.

Neglecting Social Realities: Critics argue that DPSPs overlook the intricate socio-economic realities of India’s diverse population, resulting in policies that may not effectively cater to the needs of all citizens.

Constitutional Conflict: DPSPs have led to various constitutional conflicts, including disputes between the Center and the States, the President and Parliament, and the Governor and State Legislature. Additionally, conflicts arise between DPSPs and Fundamental Rights, posing challenges in reconciling conflicting interests.

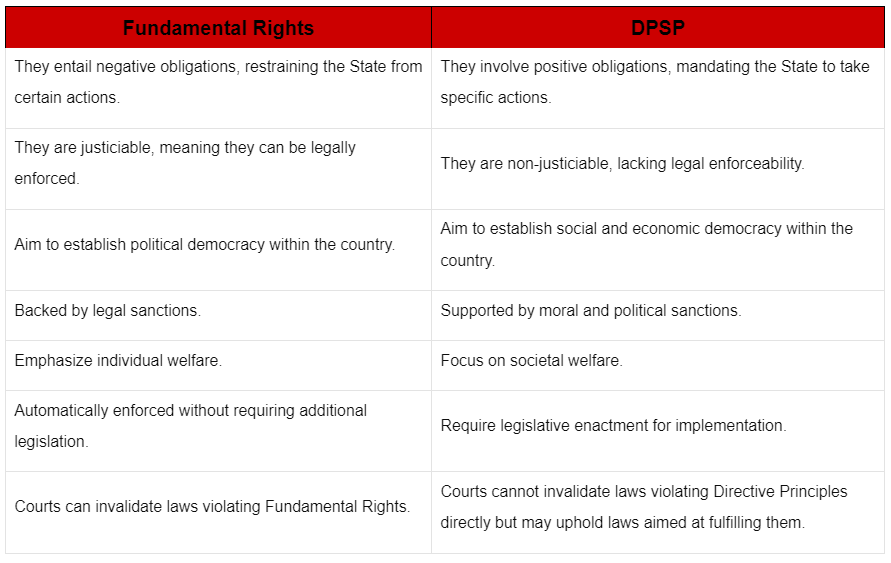

Conflict Between Fundamental Rights and DPSP

The implementation of certain Directive Principles may necessitate the imposition of restrictions on certain Fundamental Rights. This implies that the State might need to limit justiciable rights (Fundamental Rights) to enforce non-justiciable rights (DPSP). This inherent contradiction has resulted in a longstanding conflict between the two categories since the inception of the Constitution.

- In the landmark case of Champakam Dorairajan v the State of Madras (1951), the Supreme Court established that in the event of a conflict between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles, the former would take precedence. The court affirmed that Directive Principles must align with and be subordinate to Fundamental Rights. Furthermore, it determined that Fundamental Rights could be amended by Parliament through constitutional amendment acts.

- In the case of Golaknath v. the State of Punjab (1967), the Supreme Court ruled that Fundamental Rights, being inherently sacred, could not be amended by Parliament. This decision implied that Fundamental Rights could not be altered even for the implementation of Directive Principles. The verdict contradicted the court’s earlier ruling in the ‘Shankari Parsad case.’

- The 24th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1971 was enacted by Parliament in response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Golaknath Case. This amendment affirmed Parliament’s authority to curtail or diminish any of the Fundamental Rights through a Constitutional Amendment Act under Article 368.

- Subsequently, the 25th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1971 introduced a new provision, Article 31-C, which stipulated that laws aimed at implementing Directive Principles contained in Article 39 (b) and (c) would not be invalidated on the grounds of contravening Fundamental Rights under Article 14, Article 19, and Article 31. Additionally, it prohibited any law pertaining to such policies from being challenged in court on the basis of not effectively implementing the stated policy.

- In the case of Kesavananda Bharati v. the State of Kerala (1973), the Supreme Court overturned its previous Golak Nath (1967) ruling and established that Parliament has the authority to amend any portion of the Constitution, but it cannot tamper with its “Basic Structure.” Consequently, the Right to Property (Article 31) was removed from the list of Fundamental Rights.

- The 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act of 1976 expanded the scope of the initial provision of Article 31C to encompass any law aimed at implementing any Directive Principle of State Policy (DPSP), not just those outlined in Article 39 (b) and (c). This amendment aimed to elevate all DPSPs above Fundamental Rights enshrined in Articles 14, 19, and 31, thereby seeking to establish their supremacy.

- In the Minerva Mills vs. Union of India case (1980), the Supreme Court ruled that the expansion of the scope of the first provision of Article 31C by the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act was unconstitutional. As a result, Directive Principles were once again deemed subordinate to Fundamental Rights. However, the Directive Principles outlined in Article 39 (b) and (c) were acknowledged as holding supremacy over the Fundamental Rights guaranteed by Article 14 and Article 19.

- The 44th Constitutional Amendment Act of 1978 eliminated Article 31, which pertained to the Right to Property.

Present Position: Currently, regarding the relationship between Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) and Fundamental Rights:

- Fundamental Rights hold superiority over DPSP.

- However, DPSP outlined in Articles 39 (b) and (c) take precedence over Fundamental Rights under Articles 14 and 19.

- Parliament retains the authority to amend Fundamental Rights to implement a DPSP, as long as such amendments do not undermine the fundamental structure of the Constitution.

Difference between DPSP and Fundamental Right

In summary, the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) strive to achieve the principles of Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity articulated in the Constitution’s preamble. Consequently, they encapsulate the notion of a welfare state. It is this importance that led Dr. Ambedkar to refer to DPSP as the ‘novel features’ of the Indian Constitution.